Hey all, received this yesterday already, but my net-connection was giving me some uphill, so I’m posting it today. 🙂

Jasper Kent

Welcome to the South African SFF scene, Jasper! 🙂 First of all, will you please tell us a bit about yourself – the Jasper Kent that we readers don’t know?

I trained as a physicist, I work as a software consultant and my ambition has always been to be a composer. Also, I keep rats.

Can you share with us what the spark or collection of ideas was that led to Twelve?

I think it was a copy of the painting of Napoleon on the Pont d’Arcole by Baron Gros. I’d just put it up on my wall when the idea first came to me. Bonaparte looks somewhat drawn and wan in it, and I think that was what gave me the idea of Napoleonic vampires.

My first thought was to do something set in Spain, after many of the Sharpe novels, but I was also reading The Brothers Karamazov at the time, so that’s what brought Russia to mind.

Also, somewhere at the back of my mind was a story from the comic 2000AD called Fiends on the Eastern Front, which was about vampires in the Second World War. I haven’t consciously taken anything directly from that, but I think the idea of vampires in wartime has stuck with me since I read that (many years ago).

Can you give a snap-shot of what a general writing-day is like for you?

I usually get to my desk about nine and start by going through email and anything else I can find to waste my time. I’ll usually start writing about eleven. If I haven’t got going then I’ll break for lunch, but if I’m firing on all cylinders I’ll carry on straight through till about eight or nine at night, perhaps later. On a bad day, I’ll usually be happy if I get 3000 words done, but sometimes I can churn out as many as 6000-7000.

Twelve is replete with the vivid imagery that fills Russia – how did your trip go, and were there any funny or strange incidents that occurred while you were there?

I’d actually already completed Twelve before I went to Russia, though I did have time to do some redrafting based on what I’d learned. Ideally, I’d prefer to visit a location both before and after writing, but visiting afterwards allows me to be very specific about checking details. Moreover, it meant I could do some research for the sequel in advance.

Perhaps the most unusual fact about the trip was that I travelled out there all the way from England by train. There were various reasons for the choice, but one was to get a clearer impression of just how far Moscow is from Western Europe, and the journey that the French had to cover. I was in Warsaw less than a day after setting off, and yet the journey still wasn’t at its halfway mark.

The really strange thing about the journey was the fact that Russia and Belarus have a different gauge for the rails from the west. You might think that at the changeover in Brest, the easiest thing would be simply for the passenger to get off one train and onto another. Instead, they split up the train carriages and roll them all into a shed where the wagons are jacked up off the old bogies, the new ones are slid under and the wagon is lowered down again. And all this with the passengers still in the carriage! I’m glad I was forewarned.

In general, both Moscow and Petersburg were fascinating, though both have been through a lot in the last two centuries, so one has to be careful not to confuse what is and what was. Having said that, since the end of the Soviet Union there has been a lot of restoration done, often with whole buildings being recreated as they originally were.

There was one slightly spooky thing that happened while I was in Moscow. While I was in the hotel restaurant one evening, I noticed I young lady sitting at the bar, chatting up another, male guest. Since she was Russian and he was Belgian, their only common language was English, so I was quite able to eavesdrop. She was quite obviously a hooker, and so it was surprising that she was allowed to operate in a 3-star hotel. But the odd thing that I realized when they had gone was that, though I only saw her from the back, from that angle her description exactly matched that of Domnikiia, most notably the long, dark brown hair. Read Twelve to understand just how eerie that is.

What were the themes you wanted to explore in Twelve, and were these themes there from the beginning or did some of them grow out of telling the tale?

When I started writing, the biggest thematic idea I had was the idea that if you recruit soldiers to your cause who have no ideological reason for fighting with you, then once the battle is won, they may turn on you. At the time I was particularly thinking of how the Mujahedin, whom the USA encouraged to fight the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, to a degree transformed into Al-Qaeda. Whilst that feature of the plot is obviously there, I quickly gave up any attempt to press the analogy.

Ultimately, the key theme can be summed up in a single word – faith. This really came along quite late on. Although there are plenty of elements that relate to it in the plot, it only became crystallized in my mind as a major topic after an early conversation between Aleksei and Maks on the subject.

The other big theme is one that I can’t sum up in a single word, or even a phrase – so much for being a writer – and anyway, I’m not going to tell you what it is, because it would give too much away for those yet to read it.

What, in your opinion, is the fascination with supernatural beings? Immortality? A suspension of morals?

I think it is a suspension of morals, but not in an entirely obvious way. Essentially, I think that all horror – books and movies – is black comedy, and the skill is to make sure that nobody laughs (unless you intend them to – League of Gentlemen, Theatre of Blood etc.). But ultimately, nobody is expected to take it seriously – or at least to take the events themselves seriously. If you write about horrific events that are or could be real – serial killers and so forth – then you have to be much more careful about not doing anything that’s in bad taste or exploitative. Let’s face it; this is just entertainment.

Thus, I think, the use of supernatural beings allows me as an author to feel safe that the reader is suspending judgment on my own morals. Nobody is going to wonder if there is any germ of reality in the less salubrious characters I write. I think it’s similar to the reasons we tell children supernatural fairytales, not real ones.

Twelve is written in Aleksei’s voice – when writing in the first-person, have you ever found that your voice comes through more than the character’s voice?

I’m not too worried about that. Aleksei is a much bolder character than I am, so if I were to come through, it would be in Aleksei NOT doing something or NOT saying something – and that’s fairly easy to fix. Occasionally, perhaps, Aleksei does think a little too much, where others in his place would act, but that all adds to his character. Generally, if I had something to say, I’d get Maks’ to say it.

From your point of view, what is the greatest aspect of storytelling? And are there any real story-tellers left?

Before I started writing, I always thought it a bit strange when some authors, discussing their work, dwelt on this aspect of ‘storytelling’, but now I realize that, at least for my style of writing, storytelling is the key thing. Fundamentally, I’m not trying to say ‘here’s an interesting character’ or ‘this is a troublesome moral dilemma’, but ‘here’s an unusual thing that happened to some people.’ Once I’ve got the reader’s attention with that, with the desire to know what happened next, then I’ve got a framework from which I can hang all those other important things such as character and philosophy. Of course, that’s not the only way to write, but it’s how I do it.

Philip Pullman is the name that jumps to mind when thinking of a great, contemporary storyteller – also Boris Akunin. There are dozens of others too.

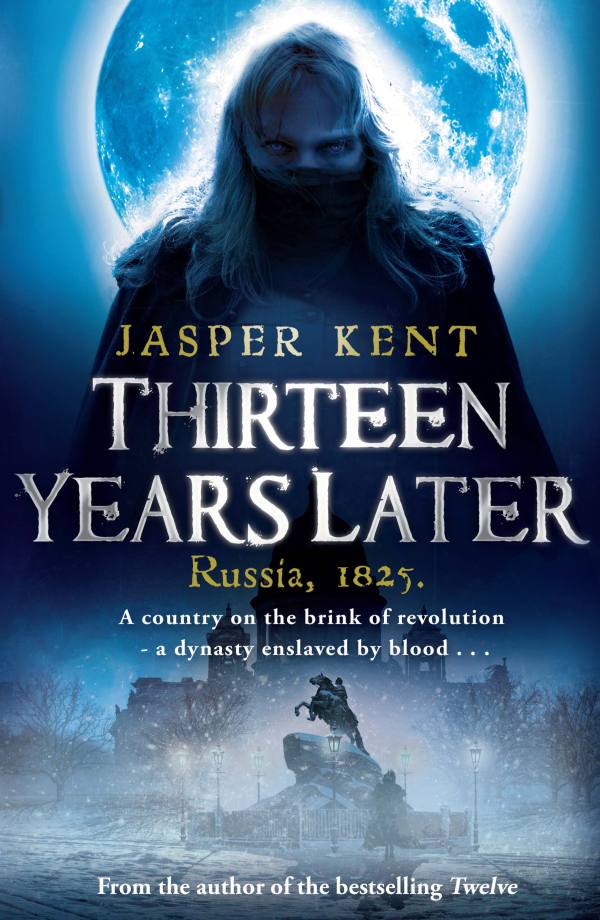

How is work progressing on the sequel to Twelve, Thirteen Years Later? And will it have anything to do with the Decembrist Revolt?

An early draft of Thirteen Years Later has just gone into the publishers, so I’m bracing myself to react with calmness and reason to suggested changes. And yes, as the name suggests, it’s set in 1825, which saw two major historical events in Russia: the death of Tsar Alexander I and the Decembrist Uprising against his successor. Aleksei manages to be involved in both.

And if Twelve could be described in a word as being about faith, then Thirteen Years Later is about resurrection.

Finally, any words of advice for aspiring writers? For instance, if you could go back to yourself at the beginning and say…?

I don’t think there’s much, if anything, I’d tell myself to do differently. I started writing seriously five years ago, and now I have a novel about to be published, so I can’t really complain, or wish I’d done it another way.

The only advice I’d give, is to pick and choose from the advice you’re given. I do some things that other authors have suggested if they feel like they’ll work for me, ignore others, and make a lot of it up for myself.

Thanks, Jasper, for taking the time to answer these questions, and we all wish you continued and greater success with Twelve and all your future projects! 🙂

Twelve

For more info on Jasper and Twelve, go to Jasper’s official website, and read my review of Twelve. 🙂